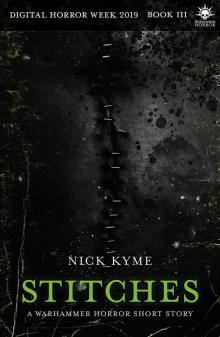

Stitches Read online

Contents

Cover

Stitches – Nick Kyme

About the Author

An Extract from ‘Genevieve Undead’

A Black Library Publication

eBook license

Stitches

By Nick Kyme

Bucher sluiced blood from the slab. Frothing, foaming, runnels spilling this way and that, it took three buckets before the water had turned from pink to clear.

‘Dead…’ he announced to no one in particular, a las-wound to the corpse’s throat leaving no doubt as to the prognosis, and moved to the next slab. Bucher checked his chrono. ‘Twenty-three hundred hours, to the second.’ He shrugged, mildly diverted.

A soldier gaped up at him from the next cot. His eyes widened in hope when he saw the stylised brass caduceus of the Imperial medicae pinned to Bucher’s red-flecked coat. He reached for him, fingers grasping like a drowning man reaches for air, but Bucher deftly stepped away. The man clutched at his chest with his other hand, where a poorly wrapped dressing, dark with blood and other less salubrious fluids, had been bound.

‘This needs to come off,’ Bucher muttered, adjusting the plugs stuffed up his nostrils. Throne, it was rank. Even the waft of watered-down counterseptic couldn’t touch the stench.

Firmly pressing down the man’s flailing arm, Bucher picked up the surgical scissors and began to cut. The bindings were tight and tough; at least a decent corpsman like Renhaus had done a passable job of patching this poor bastard up. As he severed the bandage and gauze, Bucher fancied he recognised this one. Not the name, he never remembered their names, but their parts, their roles. He always remembered that. The pieces. He was good with pieces. A vox-operator, he thought. Young, too. Barely twenty Terran-standard. Barely a man at all. Part of the Valgaast reinforcements sent to bolster the line, judging by the regimental insignia. He didn’t know much about the war, cloistered as he had been in the medicae ever since they had arrived, only that it had been raging for a long time. If the regular influx of wounded was any barometer, the breakthrough was about to happen anytime soon.

‘Let’s have a look then…’ Bucher murmured, grunting with the effort of cutting at the wrappings. Whatever was beneath had thickened the last layer of bandage, hardening it like a crust. It was like shearing through flakboard. ‘Holy Emperor,’ he breathed, exhaling in relief as he got through it.

Even before he had gingerly pulled the cloth aside, Bucher knew the boy was good as dead. That stench! Throne, but it reeked. Trenchrot had got in. And something else too. It was pupating in the exposed muscle mass, which was visible on account of the missing flesh and bone of his torso.

‘Emperor’s mercy…’ he hissed, recoiling as something beneath the skin caused it to undulate, its passage a steady but slow-moving hump. The body convulsed hard, a heavy slam resonating against the table. Still the writhing persisted under the flesh.

Bucher backed up a step, holding the scissors out in front of him, finding his own fear reflected in the boy’s ever-widening eyes.

The trooper’s voice was a shallow croak. ‘Please…’

‘I can’t help you,’ Bucher rasped. ‘I can’t…’

Another convulsion wracked the boy, sending tremors through the table, and now something was really pushing. Tiny fumaroles opened up in the skin and the gory matter beneath, venting gas and particulate. Bucher didn’t know from what. Transfixed by fear, he pulled up his surgical mask, fingers trembling, a desire to keep out whatever was emerging from the boy’s body surging forth.

Foam bubbled on the boy’s lips. His back arched, his body a bridge between the two short ends of the medical slab. The carotid artery stuck out, thick and livid, in his neck. He was choking, a gelatinous bile bubbling up from his throat. Small, black flecks like frogspawn floated in the mass.

Bucher bumped into the slab behind him, the firmness of the metal and the brush of a cold, dead hand against his skin suddenly focusing his attention.

‘Flamer in here!’ he bellowed. ‘Right bloody now!’

His fingers found the alarm and pulled it hard. Then he scrambled back, eyes locked on the boy, a shuddering, bent-backed, claw-handed image of agony.

‘Holy shitting Emperor… now…’ he whimpered, too afraid to turn his back and using the gurney rail to guide him. He yanked at the alarm until it cracked apart and broke off. He barely took notice of the siren, so fixated was he upon the boy, who turned his head and gave Bucher a look of utter despair.

‘I’m sorry…’ Bucher whispered, so quietly that he couldn’t swear he had spoken at all.

Three Guardsmen barrelled into the medicae block a few moments later, a sergeant and a two-strong team with a flamer rig.

‘Out, out!’ the officer shouted, seizing Bucher by the shoulder and dragging him back as the flamer team moved up. ‘Torch it!’

An intense roar filled the block, the heat prickling the wiry hairs on Bucher’s chin. Smoke spread everywhere. The wounded were choking on it. A couple of corpsmen had found their way in too and were ferrying out the most able-bodied. The rest burned or suffocated to death. Bucher’s last sight was of the boy’s body wreathed in flame. A smudged brown outline remained, lurching and convulsing. As Bucher was bundled out of the block he heard the very slightest suggestion of a shriek, like air escaping the narrow aperture of a balloon, just audible above the noise of the conflagration.

Bucher returned to the medicae block two days later. It had been thoroughly cleansed, though he could still detect the faint aroma of burning flesh over the chemicals, like pig’s rind and wax. He frowned, eyes narrowing at the rime of mould the ablution servitors had missed. It lurked in the tile grout, obstinate and irritating. He considered using his knife but thought better of it. His patients would probably prefer clean instruments, at least for as long as he was able to keep them that way. He took in the room. Eight fresh slabs, sluice buckets at the ready. He took a drag on a lho-stick pinched between two thin, trembling fingers. The boy’s death… That had been a bad one. One of the worst. But the war drove on, and men needed stitching up and sending back to the line. Rather here with them than out there in the dirt and the horror. Two more drags on the lho-stick and Bucher relaxed. He crushed the stub beneath his boot, sweeping a grimy coat around his narrow frame, and prepared for the slaughter to come.

It didn’t keep him waiting long.

Bodies lay everywhere in varying states of dismemberment. A heavy barrage had rolled up the line, tearing Guardsmen into ruined meat. It had hit the Valgaast worst. Most had died to the enemy ordnance. Those that hadn’t ended up in the medicae block. Bucher didn’t even know what they were fighting for, beyond the love and protection of the Immortal God-Emperor, of course. He had been shipped here like all the rest, assigned to the medicae block and that was it. No sky, no earth, just whitewashed walls, tiles and a poorly stocked refectory. He ate here, slept here, worked here. With the dead. That suited Bucher just fine.

As he cut into the trooper in front of him, Bucher reflected that he badly needed a win. His episode with the boy had spoiled his already lowly reputation. Even to think on it still made him queasy. He scratched at the back of his neck for the umpteenth time. A rash was growing there from the continued attention. It itched like hell, but hurt to touch now. He had overheard talk recently of shifting him out onto the line and a corpsman like Renhaus being promoted up to medicae primus. Elbowing him out.

‘You’d like that, you bastard…’ he muttered, cutting into flesh. It was soft, yielding. It didn’t judge him either. Blood ran almost up to his armpits he was so deep in the chest cavity, trying to tie off a bleed. After considerable effort, Bucher managed to clamp the vein and staunch

the flow but the trooper looked pale and weak. He wasn’t breathing too well either, making tiny gasps for air.

Then the breathing stopped altogether.

‘Shit!’

Bucher started compressions, not knowing if it was the bleed or something else that was causing the problem.

‘Come on, come on…’ he urged. ‘I need this.’

After a few minutes he slumped back, exhausted. A blank pair of eyes regarded him from the gurney.

And the dead man wasn’t alone. No one brought into Bucher’s care had lived. Seven dead. He knew he was incompetent, he had just thought he could convince the officers that he wasn’t.

‘They’re going to put me on the line. Holy Throne, they are…’ Trembling, he was reaching for a lho-stick tucked in his top pocket when he heard something rattle against a metal surgical dish. At first he thought it was a survivor and he turned desperately, performing a full three hundred and sixty degree rotation of the room, trying to hook his lifeline.

Nothing. Just dead eyes and slack expressions lathered in blood. But then he heard it again. A wet slap, like something soft hitting something hard.

‘What in the warp…?’

Bucher nosed around, feeling the old fear rising, one hand clasped firmly around a scalpel. The slap came again and this time he found the source, hiding behind the leg of a gurney, discarded and forgotten, a glistening red human lung.

It flopped like a landed fish and Bucher sprang back, reviled and fascinated at the same time.

‘How is this possible?’ he asked aloud. It looked healthy, and, he realised with horror, it breathed. Ever so gently, like it belonged to someone who was sleeping.

He shrank back, immediately disturbed, and reached for the alarm.

Then stopped.

Nothing stirred in the medicae block except for Bucher’s shallow breathing and the gentle motion of the lung. He felt a sudden compulsion to pick it up and examine it. Shuffling forwards again, he reached out with tentative fingers, glad for his surgical gloves. It was warm to the touch even through the thin rubber, the slow and impossible susurration of breath just audible as the lung inflated and deflated. The lobes looked healthy, the main bronchus intact. He regularly harvested the viable body parts from the men he couldn’t save and housed them in a secure locker against the medicae wall, each one kept in preservative fluid. There were a lot. Bucher had excised several organs and left them in a surgical dish next to the patient. This one had slipped off the slab somehow. It didn’t explain how it was still functioning though.

He regarded the softly pulsing organ in his hand, curious and repulsed all at once. Then he looked at the dead man lying on the gurney. The trooper’s body still lay open, its inner heat somehow cooler under the medicae’s dull overhead lamps. A thought, an insidious little idea, infiltrated his mind.

Setting the healthy lung down on a fresh surgical dish, Bucher opened the trooper up. His lung looked bad. Punctured and deflated. Bucher wasn’t sure how he’d missed it, and then he remembered how he was a poor surgeon and that this was the only explanation needed. Nevertheless, he got to work removing the bad lung and then, with a deftness he had never before displayed or knew he had, he transplanted the healthy lung. Bucher then proceeded to stitch the trooper back up… and waited.

Nothing happened, and the sudden realisation that he was expecting it to pulled Bucher from this moment of insanity.

‘What the hell am I doing?’ He rubbed his forehead, forgetting he was covered in blood and smearing it over his face. He scowled. ‘Damn it!’ Shuffling over to the wash basin, he removed his gloves and scrubbed his hands and face, annoyed at making such a stupid error and considering that he might be genuinely losing his mind. He was drinking too much. A nip here and there to steady his frayed nerves had become half a bottle and then a habit.

He stopped the meagre water flow and towelled off his hands and face. Then he leaned against the basin, arms locked and braced, head down.

Something was wrong with him. He wondered if seeing the boy, that horrible, horrible death, had marked him in some way, and it was only now that the effects of that experience were beginning to manifest. Alone and isolated in the medicae for hours, sometimes days, on end, it was no wonder he was finally going insane. He wondered how long he could go on fooling the others that he was both capable and of sound mind before they caught him and carted him off to the Commissariat or worse.

He exhaled a deep breath, then heard the sound reciprocated a few feet away.

Bucher whirled around, stray water globules studding his face and giving him the appearance of a man in a fever sweat.

The dead trooper’s finger twitched – just a last tremor of nerves, Bucher told himself, heart suddenly thumping… But then the corpse shuddered, like a ripple of electricity was rushing through the body. The chest heaved and there came a gasp, a definite lurch for air.

The trooper was breathing! Slow at first but with increasing confidence and vigour. He moved again, and Bucher gave an involuntary squeal of shock. Then the man lifted himself up off the slab, stitched up, half-butchered, but alive.

‘Medic?’ the trooper asked, blinking, a hand slipping down to the roughness of his torso. ‘Am I… all right?’

‘Y-yes…’ stammered Bucher. ‘You are, son,’ he added more confidently.

‘Can I fight?’

Bucher slowly nodded.

‘Report to the Munitorum overseer and return to the line…’ Bucher caught a glimpse of the ident-tag still hanging around the trooper’s neck. ‘Gruemann.’

Trooper Gruemann nodded. ‘I will, doc.’ He swung his legs over the edge of the gurney, barefoot and only wearing the bottom half of his fatigues but brimming with vim and purpose. ‘For the Emperor,’ he said, throwing a fervent aquila salute Bucher’s way as he left the medicae block.

‘May He protect,’ Bucher replied, still bemused but starting to feel euphoric. He approached the slab to run his finger through the blood. It was dark, thick, arterial.

‘Wounds should’ve killed him.’

That trooper had been dead. He’d seen it with his own eyes. Dead. And now he was back, and more devout and determined to serve the Imperium than ever.

‘Am I a living saint?’ Bucher asked himself aloud, stopping to marvel at his hands, his miracle-working hands. ‘A vessel of the divine Emperor?’ He laughed, mildly hysterical, and thought again about his alcohol consumption.

Then he heard something rattling in another surgical dish. Cautiously, but with growing interest, he tracked down the disturbance to a heart. Impossibly it was still beating and separate from its former owner.

There were more bodies in the medicae, cooling but not yet cold.

Bucher looked at his hands again.

A vessel of the divine Emperor.

And then he got to work.

He toiled tirelessly, stitching up the dead, filling them with animated body parts. Lungs, hearts, intestines, every organ gently pulsing in his sainted hands. He had no shortage of supplies. The death toll of the war to that point had been egregious. One by one the men arose, alive, vital and eager for the fight. Seven casualties, torn apart by mortar bombardment with little hope of recovery became seven infantrymen, ready for the meat grinder. Then seven more. And so it went.

Bucher was ebullient. Truly, he had been touched by the Emperor’s grace and given a healing gift. None left his care in a corpse-bag now. Every trooper, no matter the severity of their injuries, was patched up and sent back into the fight.

On the third week of this miraculous turnaround, Bucher received a visitor.

‘Renhaus?’ The sour look on his face said it all as he regarded the corpsman who obviously coveted the medicae’s position.

‘Doctor Bucher,’ said Renhaus, and stepped aside crisply to admit Colonel Rake.

‘Sir!’

&nbs

p; Both medical men snapped a salute, heels clicking together in the same motion.

Rake waved away the formality. He was a stout man, broad of shoulder, not wiry like Bucher but strong and born into military service. Bucher had never seen him out of his uniform, which was always pristine in the crimson and grey of the Valgaast 66th.

‘You’re to be commended, Bucher,’ Rake began. ‘Fine work you’re doing here.’ The colonel looked around, as if taking in the scene of the medicae’s recent triumphs. ‘Fine work.’

‘Thank you, sir. I serve at the Emperor’s grace,’ Bucher replied with a short, reverential bow to his commanding officer.

‘As do we all, as do we all.’ Rake straightened his uniform, his eyes firm as he regarded the medicae. ‘You’re to receive help, Bucher,’ he said, and gestured to Renhaus.

Bucher clenched his jaw so tightly, he almost broke a tooth. His heart drummed so loudly that he feared that Rake would hear it. After a few seconds he dragged out a sentence. ‘Sir, that really is unnecessary, I can–’

‘Nonsense, Bucher,’ Rake cut in. ‘You’ve practically patched up half the regiment, man. More even. We’re still in this fight because of you.’

Panic came swift and cold in the wake of Bucher’s anger. He felt suddenly feverish, his head throbbing, a whiny tinnitus forcing his eyes to narrow. Sweat slicked the back of his neck and he scratched at the wound, reopening the scab. The pain brought him to his senses.

‘I… er…’ he garbled, before the ceiling shook. Motes of dust descended earthward like little clouds of minuscule flies. Another mortar barrage had hit, providing a timely reminder of the war Bucher actively wanted to avoid. It was an ever-present companion, the faraway sound of war. Bucher felt it creeping closer. He had not known he was partly responsible for its perpetuation. It was that or death at the hands of the enemy, he supposed.

Rake raised his eyes to the ceiling, scowling. ‘Those heretic bastards are hanging on too. It’s attritional, Bucher,’ he said, fixing the medicae with the rapier point of his gaze. ‘And one thing wins a war of attrition. Men. Blood. Flesh. Bodies, Bucher. Do you understand?’

Heralds of the Siege

Heralds of the Siege The Lightning Golem

The Lightning Golem Stitches

Stitches Promethean Sun

Promethean Sun KNIGHTS OF MACRAGGE

KNIGHTS OF MACRAGGE Tales of Heresy

Tales of Heresy The Great Betrayal

The Great Betrayal Deathfire

Deathfire Sherlock Holmes--The Legacy of Deeds

Sherlock Holmes--The Legacy of Deeds Sons of the Forge

Sons of the Forge Fall of Damnos

Fall of Damnos Assault on Black Reach: The Novel

Assault on Black Reach: The Novel![[Horus Heresy 10] - Tales of Heresy Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/27/horus_heresy_10_-_tales_of_heresy_preview.jpg) [Horus Heresy 10] - Tales of Heresy

[Horus Heresy 10] - Tales of Heresy Old Earth

Old Earth Spear of Macragge

Spear of Macragge Heroes of the Space Marines

Heroes of the Space Marines Salamander (warhammer 40000)

Salamander (warhammer 40000) The Gates of Terra

The Gates of Terra Machine Spirit

Machine Spirit Salamanders: Rebirth

Salamanders: Rebirth Scorched Earth

Scorched Earth Rebirth

Rebirth Vulkan Lives

Vulkan Lives Born of Flame

Born of Flame Honourkeeper

Honourkeeper