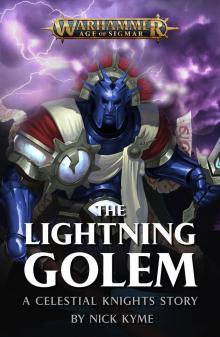

The Lightning Golem Read online

Page 2

‘They are… exuberant.’

‘Indeed. You should stay. Rest before your journey.’

Issakian considered it. He wanted to be on his way, but there were certain ties here that would keep him. At least for the night. He agreed.

‘Good. Very good,’ said Vasselius, evidently pleased. ‘And in the morning you’ll take some of my warriors with you. You shouldn’t travel alone. Not out here. Besides, they know where the mountain is. They can take you to it.’

Issakian smiled. ‘It’s almost as if you knew I would object.’

‘Did I convince you?’

Issakian held out his arm.

‘It has been an honour,’ he said.

Vasselius clasped it, and each grasped the other’s forearm in the manner of warriors.

‘No, Lord Swordborne,’ he said, nodding, ‘the honour is mine.’

Lightning speared the heavens in a brief storm of six bolts, one slightly after the other.

His head spits forks of lightning

‘You’ve lost brothers here, Vasselius. Too many.’

‘Ah, they will return. They always return,’ he said, unconcerned as they looked into the sky and tried to imagine Sigmaron somewhere beyond it.

‘At a cost.’

‘Yes,’ Vasselius nodded sadly, ‘at a cost. We are all just spirits of the lightning now, whether we choose to acknowledge it or not,’ he said, walking away.

‘And do you?’ asked Issakian, calling out. ‘Acknowledge it?’

‘Oh,’ said Vasselius, still walking, ‘I try not to worry.’

‘That sounds like wisdom.’

‘You should heed it.’

‘Perhaps I will,’ Issakian replied softly as another bolt of lightning cut the sky.

Issakian awoke, his naked body covered in sweat. The dream. Again.

And the night-clad king is no more…

The words came back, gradually resolving in his mind. He tried to steady his breathing, slow the hammering of his heart… Then he felt a light touch upon his shoulder, delicate but strong, and the pain eased.

‘I hoped you would sleep,’ said Agrevaine, and slid up beside him.

Her bare skin felt warm, welcoming. Issakian touched her hand with his then leaned over to softly kiss her fingers.

‘I did for a while,’ he said, and listened to the howl of the wind outside their tent. The leather creaked ominously; the ropes pulled but held. ‘But I am glad I can wake up to you.’

She gently turned his head, so he was facing her.

Issakian frowned. ‘You seem sad.’

‘You are leaving in the morning.’

‘And you will miss me,’ he laughed, gently mocking. Her thigh poked out from underneath the bedroll and he traced its supple curve with his finger.

Agrevaine hastily looked away.

‘You are too flippant,’ she said, angry.

‘Come now,’ Issakian replied, smiling as he tucked a strand of errant white hair back around her ear. ‘We have this night.’

‘Let me come with you,’ she said, meeting his gaze.

Issakian’s shoulders slumped ever so slightly. He shook his head.

‘I cannot ask that of you.’

‘I offer it freely.’

‘Then I cannot accept it.’

‘Then you are a fool!’

‘No,’ he said, and tenderly cradled her cheek, ‘I would be a fool if I let you. I cannot take you where I am going. I won’t risk it.’

Now it was Agrevaine’s turn to laugh. She had drawn a blade, no longer than a dagger, and held it up to Issakian’s throat. ‘It is hardly your decision. I am born of the lightning, as you are.’

‘And as fierce, I know. I don’t doubt your blade or your courage. It’s why I love you, Agrevaine. But I have seen… darkness. This portent, it bodes ill. I am bound to it, to whatever fate it leads me to. Do not force me to make you a part of it.’

Agrevaine glared, but after a few moments relented.

‘Damn you,’ she murmured.

‘I will admit,’ Issakian said, eyeing the blade warily, ‘this is not how I thought this would unfold.’

Agrevaine scowled, but lowered the knife.

‘We have this night,’ he said softly.

‘We do,’ she whispered, drawing close to him. ‘My blood, the thunder…’

‘My heart, the lightning.’

The flap of the tent parted, prised loose by the wind. Night scents washed in, redolent of wood smoke and presaging rain. Issakian and Agrevaine barely noticed as they drew together, their bodies limned by the moonlight.

The mountain rose up in the distance, a monstrous and ugly thing. Its five peaks did indeed put Issakian in mind of a clawed hand, and he scowled at the thought of it.

‘How far?’ he asked as a scout alighted on the rocky promontory where Issakian had made his vantage.

‘Another day hence,’ came the gruff reply, the scout folding lightning-wreathed pinions behind his back as he approached the Lord-Veritant. His name was Leonus.

Issakian nodded. ‘Good. I’ll not fail again.’

‘Do we rest tonight?’

The night drew in, sweeping soft and deadly. Issakian briefly thought of Agrevaine, but the memory faded quickly with the calls of the nocturnes, the beasts that preyed in the darkness. One such creature turned on a spit, its flensed flanks cooking slowly. The smell was not appetising but it was still meat.

Issakian’s eyes were drawn to the meagre feast, and to the eight warriors sat around it whose armour glinted gold in the firelight, their violet spaulders dark like patches of twilight.

One of the warriors looked up. Vitus. He had a recent scar that went from cheek to brow in a ragged line. Like the others’, his sigmarite armour was chipped and hastily repaired in places. A shrine stood nearby. It was just beyond the glow of the fire, but still visible. It comprised a notched shield, strapped to a sword that had once belonged to Lord Brightclaw. Marks had been cut into the shield’s face. They numbered almost thirty now.

Issakian met the hardened gaze of the warrior and felt the smallest pang of regret. They were not the first to die in service to his quest. He felt the tremor again in his left hand, his lantern-bearing hand, but mastered it. Vasselius’ words returned to him. We are all just spirits of the lightning now.

That seemed a lifetime ago.

‘Let’s eat, Leonus, and march again in the morning,’ Issakian told the scout.

‘Should I post a watch, Lord Swordborne?’

Issakian looked out into the darkness. His eyes took a moment to adjust after staring at the fire, but eventually he saw the shadows of the nocturnes creeping in. Long-limbed, with grey, pallid skin and lamprey mouths, they chattered excitedly as they drew nearer.

‘We won’t need it. They’ll be upon us soon.’

A cloying mist lay upon the ground the next morning as five warriors reached the foot of the mountain. A narrow pass led to a cleft in the mountainside, the only way in that Issakian knew of.

A hollow wind blew through the pass, cold and desolate. It sang to the Stormcasts’ heavy hearts.

Issakian looked to the peak. Between wreathes of cloud, a slate-grey sky promised snow.

‘We should not linger,’ he told Vitus, who had taken up position just behind the Lord-Veritant. ‘It’s half a day through the pass, and if snow comes it will be treacherous. And without Leonus to watch over us from above we could be easy prey.’

Vitus called to the men, declaring a forced march up the pass.

They left all unnecessary trappings behind, their food and shelter, spare weapons. A sigmarite treasure hoard glittered in their wake, a notched shield and sword sat on top like a sacrificial offering.

Issakian entered a large cavern through a jagged mouth of stone in th

e mountain. He was glad to be out of the wind. Snow clung to his cloak like mould and he brushed it loose.

The storm had risen swiftly and without warning. As Vitus and the other two survivors joined him, Issakian lifted his lantern.

Sharp, gilded light described a grand chamber. Its depths went well beyond the lantern’s reach but at the periphery of the light, a host of ivory statues looked on stoically. They resembled warriors, but of an order unknown to Issakian. Stone flags defined a processional that led to a throne. Upon it sat a knight in frostbitten trappings. He wore a tabard over his armour, the sigil of a chalice still discernible despite its threadbare state. His skin was deathly grey and rimed with thick ice. The crown upon his head suggested nobility. A sword rested in his hand, the blade touching the floor. A shield sat against one arm of the throne and displayed the knight’s heraldry, a lion rampant.

Issakian was about to make for the throne when he felt a hand upon his shoulder.

‘What is it, Vitus?’

He gestured to the ground where the shadows grew thickest.

‘Bones…’ he murmured. ‘Some beast has made this place its lair.’

‘It may have moved on,’ suggested Issakian, ‘but we take no chances.’

The Stormcasts drew their weapons and the air sang to the crackle of sigmarite.

‘Spread out,’ said Issakian. ‘Search this place. I will have an answer. I must have an answer.’

Warily, they began to search the chamber. Breath misted the air through the mouth slits of their helmets.

Issakian reached the throne and crouched down by its incumbent, surprised at how well the knight had been preserved. His greying skin suggested profound age. It had not decayed though, merely withered.

Then he spoke.

Issakian recoiled in shock.

‘You should not have come…’ the knight rasped, the voice of a revenant. ‘Turn back… Turn back…’

If the others had heard this, they gave no sign. Issakian looked up and caught the figure of Vitus disappearing into the darkness. He returned his attention to the knight.

‘How are you alive?’ asked Issakian. ‘Are you cursed?’

‘Turn back… You should not have come.’

‘I cannot. This is my path. I have sworn to find the Summoner, the purple crow. Tell me, what do you know of it?’

‘Turn back… or be consumed by the lightning golem.’

‘I fear no monster. I have killed many to get here. Know that I will not relent. I have already lost so much. This place came to me in a vision. You are the only living thing in this mountain. Now. Tell me!’

The knight grasped Issakian’s vambrace before the Stormcast could stop him. He tried to free himself, but the revenant’s grip was strong.

‘You doom yourself, warrior,’ he said, and regarded Issakian as if for the first time. ‘What manner of champion are you? I have never seen the like, but then I have dwelled here for what seems like aeons. Are you here to break this curse, I wonder?’

Issakian tried to answer, but his tongue felt leaden in his mouth. A cold vice had closed around his body and drew tight.

‘Find him…’ said the knight. ‘Kill him.’

‘W-where?’ Issakian snarled through clenched teeth.

The knight smiled as coldly as a winter storm.

‘Closer…’ he said, ‘and I will tell you.’

Issakian leaned in and listened as the knight whispered into his ear.

A low rumble sounded from somewhere in the depths. Then came shouting and the clatter of blades.

Issakian looked up, startled. The pain lifted. He was free. It was as if the knight had not moved at all, and Issakian began to question if what he had experienced was even real.

‘Turn back… You should not have come.’

‘Turn back!’ he cried out to the others, standing and about to raise the lantern. He was too late.

A Stormcast flew across the chamber, hitting one of the statues and shattering it. He crumpled in a heap of broken stone and sigmarite. He tried to rise, reaching for his hammer but fell back, his breastplate a red ruin of protruding bone. The lightning arc hurt Issakian’s eyes as it hurtled skywards and tore the ceiling in half.

‘Beast!’ roared Vitus, emerging from the shadows at a run. Another warrior followed a few paces behind, unleashing crackling lightning arrows at something huge and looming behind him.

Realising his arrows could not prevail, the archer turned. A massive hoof crushed him before he could flee any further.

The beast reared up, its shaggy hide thrown into stark relief by a bolt of coruscating light from the archer’s death. It bellowed, half in pain, half in fury, a feral snarl upon its brutish face.

‘Stonehorn!’ Vitus yelled, brandishing both swords as the beast towered over him.

Armour festooned with studs and spikes sheathed its muscular shoulders, but the true threat lay in the long horns that protruded from its snout. Formed of overlapping plates of hardened bone, they curved into a wicked points as sharp as flint-ice.

It stank of dank places, of hoarfrost and dead meat.

And it wasn’t alone.

Another stonehorn thundered out of the darkness. It stood before the entrance to the chamber, crushing any hopes of retreat.

The cavern had begun to collapse. Hunks of rock plummeted from the roof. One struck Vitus, who fell to his knees. The first stonehorn gored him through the chest, piercing his armour as if it were parchment not thrice-blessed sigmarite.

As Vitus died, Issakian wrenched off his helm and touched his sword to his lips.

‘For Sigmar and Azyr,’ he breathed, provoking an old memory. ‘Agrevaine…’

He caught a last glimpse of the ancient knight before the end, silent but his lips moving to form a familiar phrase.

Turn back… You should not have come… Turn back…

And then the mountain collapsed and Issakian had but a moment to consider the knight’s words before the rocks crushed him.

‘We should turn back…’

Endal Cogfinger hung from the rigging with one hand, his iron-shod boots braced against the raised lip of the foredeck. He held a spyglass against the left eye-lens of his mask and leaned out fearlessly into the wind.

They rode low, skirting the crests of lava waves. Fire caressed the keel of the Drekka-Duraz and cast its golden filigree in a hellish glow. A stern ship, laden with guns and with a rune-etched hull formed of steam-bolted plates, even the ancestor figurehead at its prow snarled.

A smouldering, undulating landscape stretched out in every cardinal direction and as far as any mortal eye could see. The Magmaric Sea writhed below, spitting flame and geysering smoke, as volatile and unpredictable as a battlefield. Red-tinged clouds glowered overhead, close to the dirigible’s upper fin, a roiling mass of angry cumulonimbus, threaded with bursts of lightning that lit their insides like incandescent veins.

‘Bah, is it water or iron in your stomach, lad?’ asked Fulson Aethereye. ‘Your father, I swear by the Code, would never have baulked from a storm.’

‘It is no ordinary storm, Fulson,’ said Endal. ‘See for yourself.’ He handed him the glass, but the ship’s aetheric navigator had one of his own.

‘Keep your trinket, arkanaut,’ he grumbled, and took out an arcane device from his trappings. He glanced over his shoulder at the frigate’s sole passenger and muttered proudly, ‘Zephyrscope.’

Fulson also wore a mask. Wrought from iron, chased with gold, it resembled a duardin face. The beard curled, unnecessarily extravagant. The left eye-lens telescoped to examine a sphere clasped to the end of a complex metal armature – the aforementioned zephyrscope.

‘The aether currents are turbulent,’ he admitted. ‘This deep into the firetides… the updraughts are unpredictable, captain. Lad might have a point.’

> ‘I have been told,’ interrupted the passenger, ‘that the Kharadron do not renege on a bargain once one is struck.’ Issakian Swordborne turned his head to regard the ship’s captain. ‘Or am I mistaken?’

Arms folded, legs braced apart, Zhargan Irynheart looked down from the forecastle at the main deck, where the Stormcast and most of his crew were standing.

Issakian felt the anger in the captain’s stare, even behind the duardin’s mask.

Embers crackled on the hot breeze, underpinning the silence. Ash and cinder lay thick on air that had become hard to breathe.

‘Half before, half after,’ Issakian reminded him, unflinching before the duardin’s contempt. ‘That was our agreement. Do you deny it?’

Zhargan’s mask was more ornate than that of his crew. It signified seniority. His ship, his law.

‘We’ll see it done,’ he growled. ‘Let it be known that no ship of Barak-Urbaz ever refuses profit. But no purse is worth the destruction of this vessel. I’ll sooner throw you to the firetides than court that fate.’

If Issakian felt anything about the thinly veiled threat, his helm hid it well enough.

‘You will be well compensated for the risk.’

‘Aye,’ said the captain, ‘but unlike the blessed of your God-King, we duardin are not reborn from thunder and lightning. We are not so profligate with our lives, Stormcast.’

The ship pitched to its starboard side, dragged by a violent aether current, but soon righted again. The Kharadron hardly seemed to notice. Nor did Issakian.

‘You sound afraid, Irynheart. Are you?’

The arming of several aethershot rifles clacked noisily as the Grundstok Thunderers on the main deck took exception to the slighting of their captain.

Issakian held still. He clenched his left hand to stop it from shaking.

Zhargan waved them back. ‘Six guns aimed and you scarcely take a breath. It’s true then, is it, that your kind have lightning instead of blood running through your veins?’

‘I asked if you were afraid.’

Zhargan gave a slow and rueful shake of the head.

‘Yes, I’m afraid. Any sane person would be. You’ll need to do better than that to raise my ire, though.’

Heralds of the Siege

Heralds of the Siege The Lightning Golem

The Lightning Golem Stitches

Stitches Promethean Sun

Promethean Sun KNIGHTS OF MACRAGGE

KNIGHTS OF MACRAGGE Tales of Heresy

Tales of Heresy The Great Betrayal

The Great Betrayal Deathfire

Deathfire Sherlock Holmes--The Legacy of Deeds

Sherlock Holmes--The Legacy of Deeds Sons of the Forge

Sons of the Forge Fall of Damnos

Fall of Damnos Assault on Black Reach: The Novel

Assault on Black Reach: The Novel![[Horus Heresy 10] - Tales of Heresy Read online](http://i1.bookreadfree.com/i/03/27/horus_heresy_10_-_tales_of_heresy_preview.jpg) [Horus Heresy 10] - Tales of Heresy

[Horus Heresy 10] - Tales of Heresy Old Earth

Old Earth Spear of Macragge

Spear of Macragge Heroes of the Space Marines

Heroes of the Space Marines Salamander (warhammer 40000)

Salamander (warhammer 40000) The Gates of Terra

The Gates of Terra Machine Spirit

Machine Spirit Salamanders: Rebirth

Salamanders: Rebirth Scorched Earth

Scorched Earth Rebirth

Rebirth Vulkan Lives

Vulkan Lives Born of Flame

Born of Flame Honourkeeper

Honourkeeper